At 8.30am on Monday, 9th October, 1972, I entered a Brave New World – Basildon.

Although that comparison to Aldous Huxley’s sci-fi classic would cast me in the role of the Savage whereas I felt I was the explorer in a concrete jungle.

The drive from Burnham-on-Crouch, where I was living in a rented caravan for two weeks, allowed me to see the gradual change from rural Essex to the urbanisation and mid-century Brutal architecture.

By the time I reached the centre of Basildon New Town I found myself longing for the company of others as I took on the role of Welsh journalist/explorer Henry Morton Stanley seeking Dr Livingstone.

I drove into the car park which lay behind Southernhay and positioned my car opposite the back door of the Recorder office.

Within minutes I saw a bearded figure heading for the back door and was 99 per cent certain I had seen him in the editorial room when I came for my interview.

I got out of the car, locked the door and followed him in.

The door opened onto a corridor with a kitchen to the right and what were probably toilets to the left. Ahead was an open door and I went in to the editorial room where I was to be working for the foreseeable future.

As I entered the man I had followed in turned and, with a smile on his face, said: “Ah Robin isn’t it? Welcome to Basildon and the Standard Recorder. I’m Barry Brennan the deputy editor. Tony won’t be in for a while, he’s at head office.”

After shaking my hand he introduced me to others in the office: Bobs Hurley, a slim, clean-shaven man in his 30s, the chief reporter; John Howard, a short bearded man, senior reporter; Peter Biscoe, about my age, slightly heavier in build, reporter; a man whose name I cannot remember to this day (even though he was to get me into trouble with my future wife and her friends), sub-editor; and a gray-haired woman, Elizabeth, who worked part-time and whose husband had been the staff photographer who had died a year or two before.

With introductions made I was shown my desk, an old-fashioned wooden table-size desk with two drawers to the right hand side, on it was an old sit-up-and-beg typewriter, a cream-coloured phone, and a wire filing basket.

It was in a corner which put my back to the partition between editorial and reception and had me facing across the other desks to where Bobs sat at his own desk keeping an eye on the reporters.

Barry showed me the stationery cupboard filled with all the paraphanalia a good journalist needed: notebooks, pens and pencils, copy paper, carbon paper, typewriter ribbons, paper clips and staplers and staples.

I was shown the kitchen which had all the makings for tea and coffee and the spare mugs for general use; the toilets, opposite, and the darkroom. I was told I would meet the photographer later.

After the general introduction Bobs gave me my first of many assignments – a trip over to Billericay to cover the local court.

Bobs told me there were two courts running that morning, a regular court and a juvenile, both starting at 10 and both having good cases running.

“You’ll meet Julian Barnes from the Billericay office there. He’ll cover the main court and you can deal with the juveniles. It’s alleged some young lads beat up a man and left him at the side of the road.

“Julian can fill you in on the magistrates, court officials etc. He’s a good lad and I’m sure you’ll get on.”

Driving from Basildon to Billericay was a reversal of the morning journey, taking me from the concrete jungle back to genteel civilisation in a proper little market town.

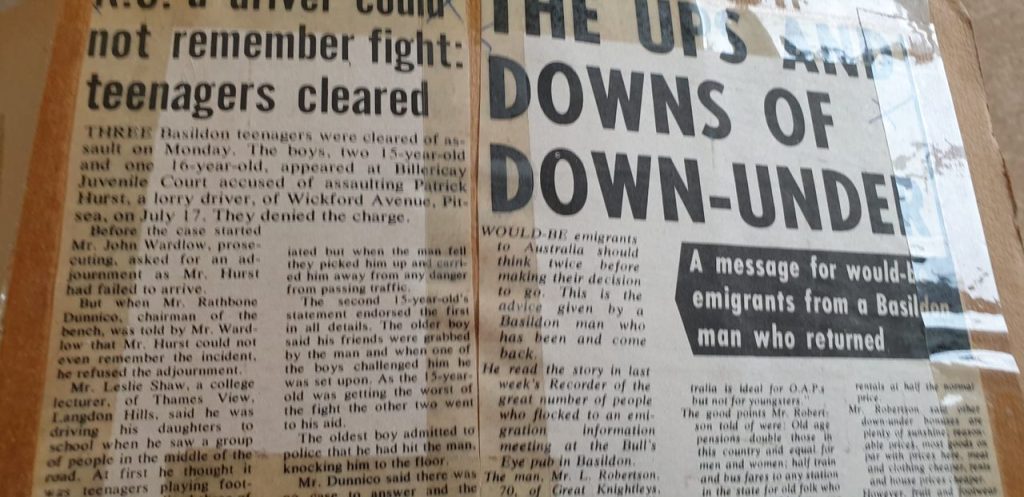

The juvenile court was straight forward and it turned out the lads before the court were more victim than aggressor.

Rather than setting on the man one of their number had actually been grabbed by the man, a lorry driver, and hit. Seeing their friend being beaten they went to his aid and eventually chased him off.

Also they had not dumped him at the side of the road, as claimed by a late-arriving witness, they had picked him up when he fell and took him to safety at the side of the road.

The “victim” failed to turn up at court and the magistrates were told he had no recollection of what had happened.

The magistrates decided there was no case to answer against the boys, two aged 15 and one 16, and the case was dismissed.

During that week I did the emergency rounds – police, fire and ambulance; sorted out and wrote up recollections of older townsfolk from the war (including the rector and his family who were unscathed when the rectory was hit by a bomb); wrote up my fist story on the battle between older residents and the Basildon Corporation over compulsory purchase orders; interviewed a businessman who had been dumping rubbish bags at the council offices because thy hadn’t put up proper signs to the tip and people were dumping rubbish in his boatyard; and even interviewed a 70-year-old man who had recently returned from Australia, where he had lived for five years, and said it wasn’t as good as it was cracked up to be (the previous week the paper had reported on the large number of people who had turned up at a meeting about emigration).

It was a good and varied first week in my new job but as I read the paper that Friday and checked off my contributions little did I know what would soon be coming my way.