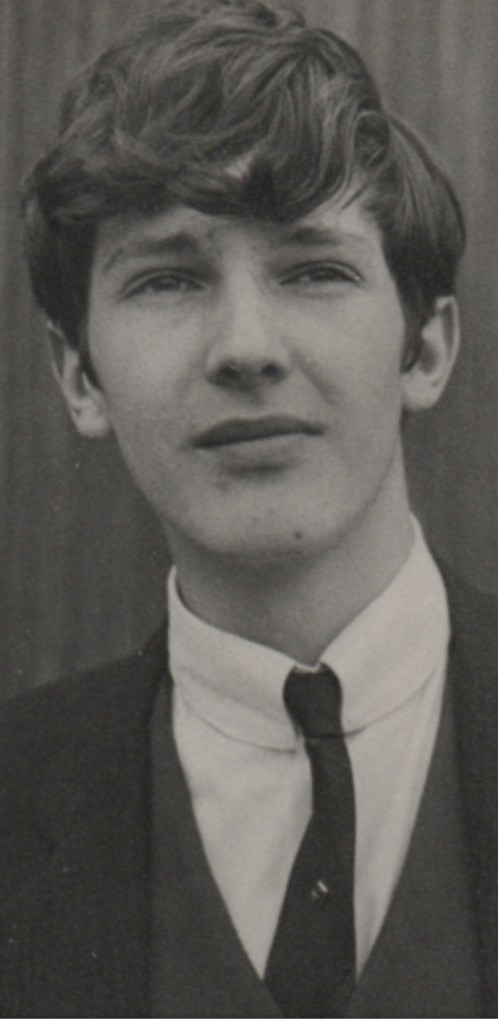

All the way home after my “little chat” with the headmaster I was wondering what to say to my parents and how they would take it.

I wasn’t worried. I wasn’t frightened. My father was a big man. He was also a gentle man. He never raised his hand in anger.

Considering all he had gone through earlier in his life it was surprising he was NOT filled with anger.

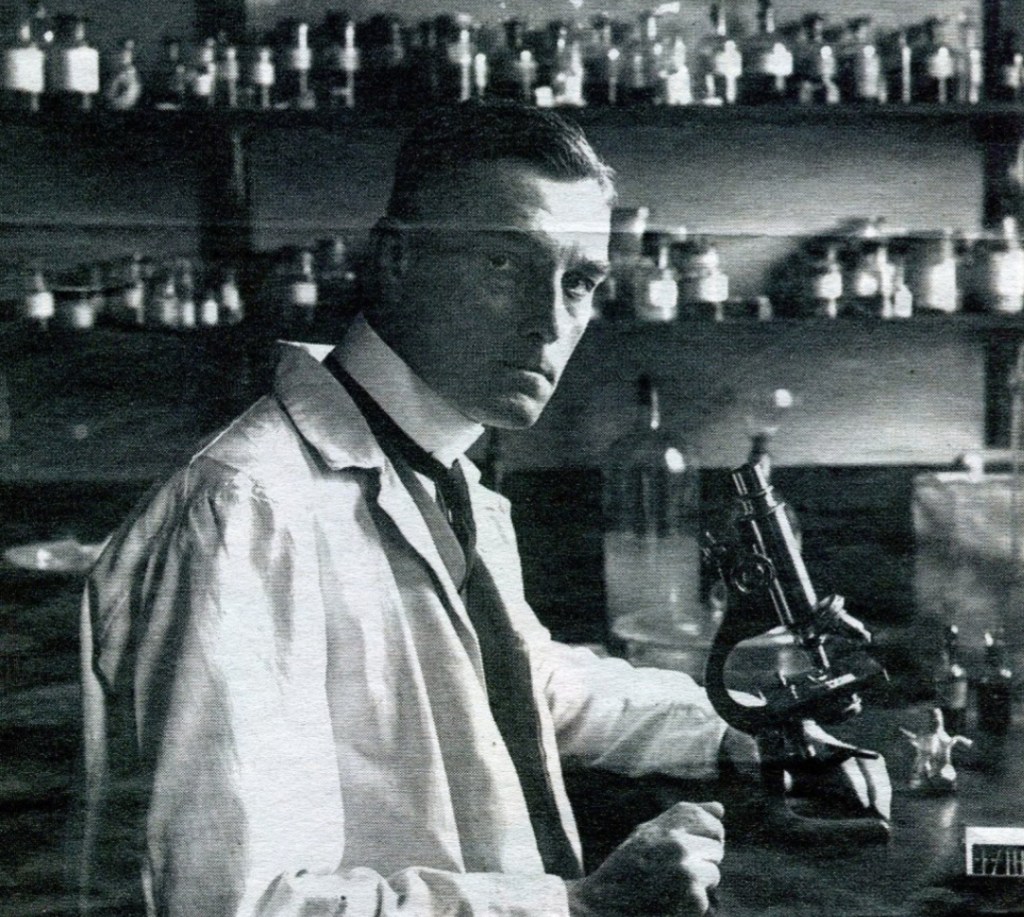

My father was born during the Great War in 1915 the youngest of four children, two boys and two girls. His father, Rev Edward Vyrnwy Pierce, and his mother, Catherine nee Crocket, were everythig to their children and their oldest daughter Dorothy was young David’s “big sister” in every possible way and he called her Dodo.

In the late 20s Dorothy left Grove Park Grammar School and went to Bangor Unversity to study to be a teacher.

David hoped to follow her to Bangor to study classics.

After her graduation in 1932, when David was just 17, she hung herself in her rooms at the university.

Their mother never recovered from the shock and heartbreak and died the following year.

This left David home alone with his father, his siblings had already left home and begun their lives.

University was now a forbidden word in the house of mourning.

Meeting my mother made all the difference to him.

These were the people I was cycling home to tell that I had been involved in a difference of opinion with the headmaster and had defied his authority.

As it happened they both took it reasonably well. It wasn’t as though I hadn’t caused them plenty of concern in my 15 years, with all sorts of scrapes. Putting a stink bomb in a solicitor’s car was the least of them.

Naturally they knew something was up by the time I got home. A telephone call had covered the mile faster than I could cycle.

What they didn’t know were the details. The headmaster’s secretary had simply said he wanted to speak to them the following day.

Dad had an office behind the shop, linking to the kitchen. He needed to keep an eye on the shop as it didn’t close until 6 and so the great discussion took place there.

I explained the situation so far to my parents and finished by saying I was not going to stay down a year and if that was what the head intended for me then he was out of luck – or words to that effect.

Afer listening to everything I had to say there was silence and my parents looked at each other and then my father said: “Well what are you going to do with yourself now then? If you don’t go to school how will you study? You will need some form of educational certificate or you will find it a hard slog ahead.”

“I’m not going back.”

“OK. We’ll take that as read. So what do you want to be? A shop assistant? A clerk in an office?”

“I don’t know.”

“Let’s say you don’t go back. I don’t mind what you decide in the end. You can travel the world if that will make you happy but what will you do when the travelling comes to an end? You need something to fall back on. You need something to show, even if it is just a piece of paper with an official stamp on it. What do you enjoy other than science?”

“Writing. Words. William Shakespeare.”

It was not a brilliant start but it did begin a conversation.

It took time but somehow, without knowing how I had got there, I found myself saying: “I want to be a journalist.”

That was a significant moment which set me on a course not just to my future career but also to my political enlightenment and to meet the love of my life.

For many years I firmly believed I made that decision and settled the course of my life then and there.

It was many years later I realised my father had never believed I would have settled to a scientific life and knew that my future lay with words.

He was right.

It was initially a tortuous road.

I don’t know how but I did not go back to school; my parents signed me up with a correspondence course and I studied for four GCEs from home but sat the actual exams at my old school – I was the only one not in uniform.

I know I studied English Language and Literature as well as history but I don’t remember the fourth subject.

It was an interesting time during that period from May 1965 to June 1966. I probably worked harder than I had done at school because now I was in charge. Well my parents were technically as this was home schooling but I wanted to make a success of it.

I still had the theatre, which in its way was part of my education, and my books, and the library and my friends at weekends.

I was happy.

Defying the headmaster only made it sweeter.