The next day I arrived at the office earlier and, after parking my scooter, I went to a nearby newsagent shop and bought a copy of another local paper (the Flintshire Leader), a copy of the Daily Mirror and a copy of The Guardian . . . and a packet of cigarettes.

I went straight up to our office, or the reporters’ room, whatever you wanted to call it, and put my crash helmet, goggles and gloves on the low cupboard top where the newspaper files were.

I lit a cigarette and stood looking down the High Street as the town bustled into life below me. I could see the town hall on one side and shops the other.

There was a big pub, also on the right, (I think it was called The Crown) and some other businesses. I decided if today turned out like yesterday then I would take a walk along the High Street later in the morning.

Delwyn arrived a few minutes later and we headed downstairs to see Bill.

He was sat at his desk with a cigarette burning in the ashtray.

“I’ve checked the copy you typed yesterday and it all looks good. You’ve stuck to style and there were only a couple of errors which I amended.

“Now for today. Who enjoys sport?”

I was quick to respond: “Playing or watching?”

I was actually quite keen on certain sports. Rugby had become a passion, naturally, and I had played a bit at school. My real interest at the time, however, was hockey.

When I had first been introduced to hockey at school I had taken to it like a duck to water and I quickly showed a preference for the Indian head as opposed to the English head.

When I mentioned to my father that I needed my own stick for the second year he immediately recommended the Indian head.

It turned out that during the war he had played hockey for an RAMC side when stationed in Egypt and had been quite proficient.

Delwyn said: “I like football and cricket, prefer to watch rather than play.”

This seemed to meet Bill’s approval: “Well you can take a shot at typing up the sports reports we’ve had in from local clubs. You’ll see the style to follow in the files.

“Don’t use every jot and tittle they write. They tend to play up most of their reports and most can’t spell for toffee.

“There’s a stack of them dropped off yesterday and this morning. They’re in that basket over there. Take them up and get started.”

After Delwyn had left the office Bill turned to me: “I don’t think you are a sporty person are you Robin? There was a hint in your response.”

I admitted that beyond hockey, rugby and darts, there weren’t many local club sports I was that bothered about, and I only supported Liverpool FC because it was a family tradition on my mother’s side.

“Well there are probably lots of things you won’t enjoy but will still have to report on but in this case I had a willing volunteer.

“We don’t just get sports reports sent in. We also get the WI, Scout and Guide reports and similar club activities. There’s a pile of those in that basket and the same goes for those as sport – follow the style in the paper.

“I’ll be going to the magistrates’ court at 10 and I’ve got some other meetings to attend and won’t be back until after three.”

With that I realised I had been dismissed so I grabbed the pile of association reports and headed upstairs.

The previous day I had laid claim to the window end of the table desk, meaning I had the light from the window over my shoulder and not in my eyes.

I put the stack of reports by my typewriter, put my jacket over the back of my chair and said: “Fancy a coffee Delwyn? I’m just going to get myself one.”

He nodded a yes and I headed downstairs.

Once we were sorted out with coffee and copy we started tapping away. My typing lessons stood me in good stead, even though I had only scraped a Pass in touch typing. I could at least retain a couple of lines at a time in my head and amended spelling and grammar as I went along.

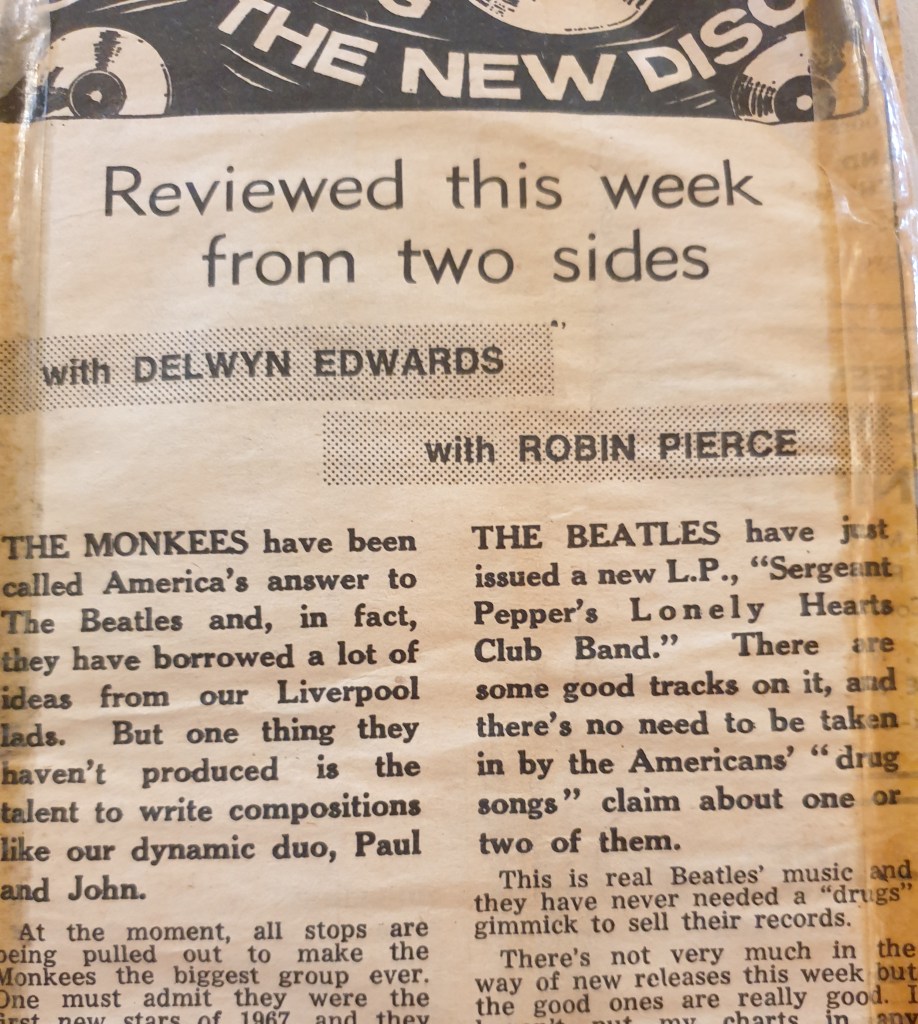

By mid-morning we were ready for a coffee break and Delwyn did the honours. I took my copy of the other local newspaper and started going through it.

Initially I was comparing stories, page leads, secondary stories, even weddings, funerals and social items.

One thing I did notice was that our paper had more court stories with fuller details. Some of the opposition court pieces were little more than names, ages and addresses; charges; pleas of guilty or not guilty; verdicts and sentences. Sometimes they ran similar cases together, such as tv licence prosecutions.

I also read through the Mirror and The Guardian to compare a “working class” newspaper and a “middle class” newspaper. This was a more complicated comparison and I decided to leave that until I got home.

We worked on until lunchtine again and once more I headed down the hill for a pint with Roger.

In the afternoon, if we didn’t rush the reports available, we had enough to keep us going until 5pm.

About twenty past three we heard Bill return and a few minutes later we heard his typewriter clattering away in the office beneath us.

As it happened I finished all my reports by 4pm and had double-checked the copy as well so I continued with comparing our newspaper with the opposition.

It wasn’t too difficult to see which reports had been sent to both newspapers simply by the order and wording in which they were presented.

Just before five we went down to Bill’s office and handed him the sheaf of reports we had done.

Over the two days we had probably typed up enough to fill at most two broadsheet pages, even allowing for adverts.

I wondered how much of the rest of the news was going to come from Bill and where he was getting his stories from.

We handed our copy to Bill and he quickly looked over it before telling us we might as well head home.

When I got home this time I took my two daily newspapers and also took my parents’ newspapers, the Express and the Mail and started running a four-way comparison on which stories appeared in all newspapers and which only appeared in one or two.

If I didn’t get much direction at work I intended finding out as much as I could for myself.