My one failing as I prepared to become a journalist was getting to grips with Pitman’s shorthand.

Out of our class of less than 20 on my Kelsterton College course myself and four of the girls could not grasp the Pitman system.

I don’t know if it was a means of letting us down lightly but the shorthand tutor said that mastering Pitman’s was not a means of measuring intelligence. Some of the cleverest people around could not grasp it.

Personally I did not care if people doubted my intelligence based on a writing system which appeared to bear no relation to written English.

I would have said that all my fellow students at Kelsterton had a decent degree of intelligence and I wouldn’t have been able to differentiate between Pitman successes and Pitman failures.

My lack of shorthand did not prove a major problem as I started work.

Note-taking is important, especially in council and court reporting. Nowadays “journalists” tend to use recording devices (mobile phones in the 21st century) but this does take a long time to run back and forth.

I started to make my own version of shorthand – not much use if anyone else wanted to read my notes but then again my handwriting was nothing to shout about – beginning with dropping vowels and using accepted abbreviations such as “tt” for “that” and an ampersand (&) or a plus sign (+) for “and”.

This worked well and once I started to cut the letters down to simple strokes I found I could produce an acceptable and readable set of notes.

I knew shorthand was an important part of the NCTJ Proficiency Test but I thought I would cross that bridge when I came to it.

As it happened the NCTJ had just that year ditched Pitman’s (invented by Isaac Pitman in the 1850s) and were trying out a new system invented the previous year (1968) by James Hill – this was Teeline.

As soon as I received my first Teeline textbook I felt immediately at home.

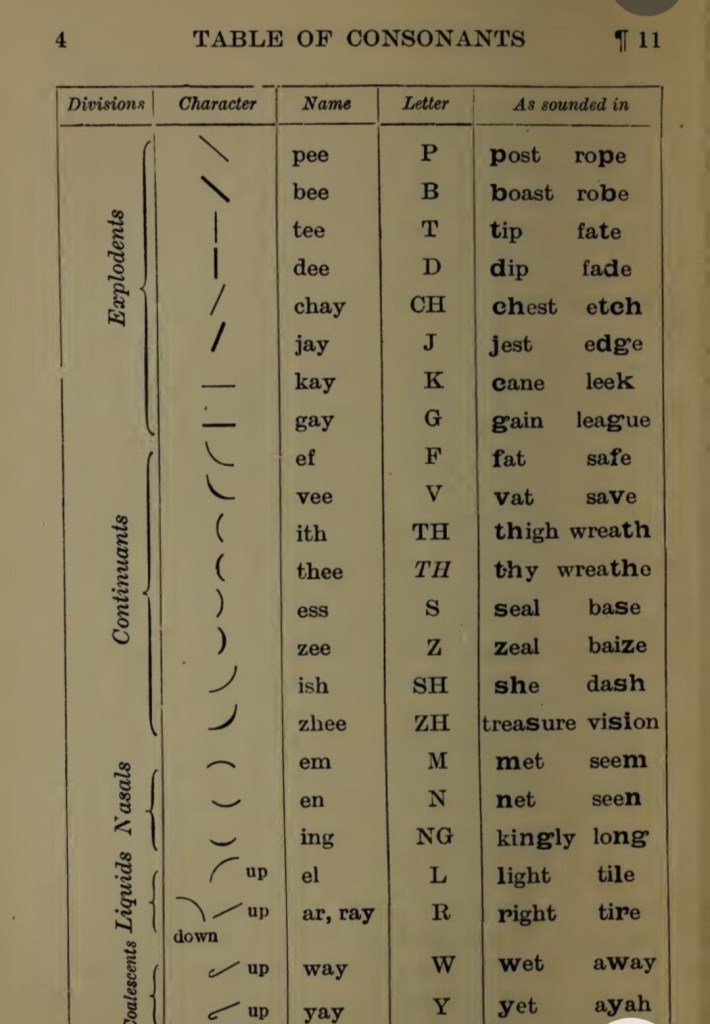

Instead of this:

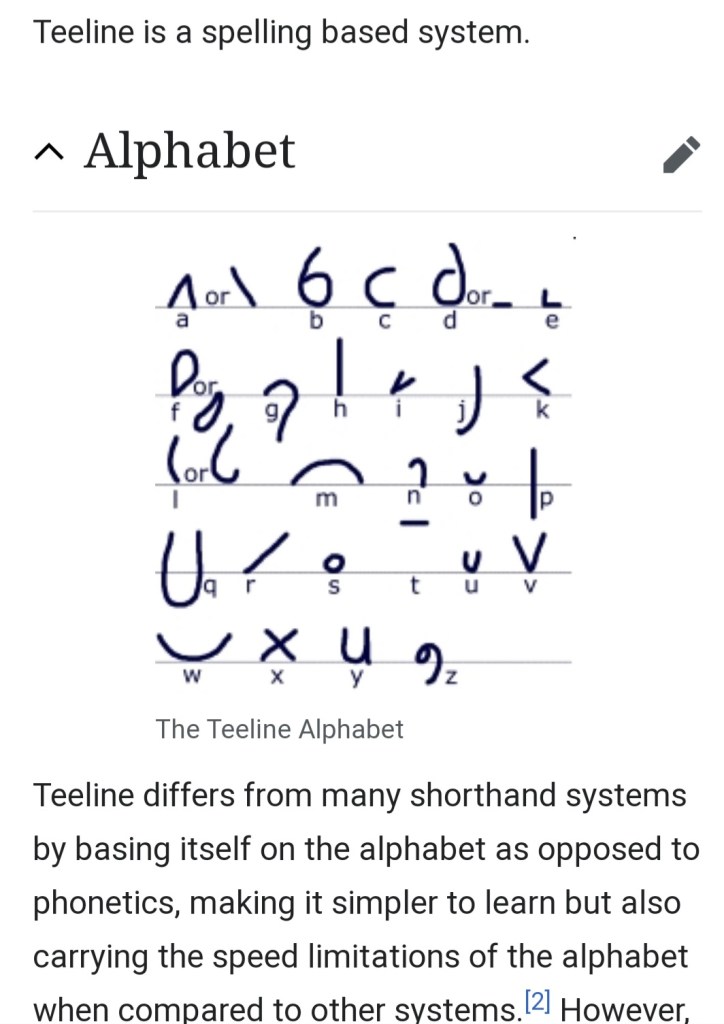

We had this:

Basically Mr Hill had codified the method I was using. Simplified letters with unnecessary vowels and consonants removed.

It normally takes a year to learn Pitman’s (Hill was a Pitman’s teacher who was almost 60 when he came up with Teeline) – after the eight-week first course I was at a perfect 90wpm and 95% on 100wpm over a five-minute dictated speech.

Like a duck to water.

Others also picked up quite speedily and we even contributed suggestions re certain letter combinations which were passed on to Mr Hill.

(I believe James Hill died a couple of years after our course but his work was continued by IC Hill who might have been his wife, sister or daughter – Ivy Constance Hill)

A couple of people on the course did struggle at first with Teeline and I later found out they had both of them studied and mastered Pitman’s.

For the rest of us we had no previous method clogging our minds (I had put my failed Pitman’s attempt completely out of my attic of memories).

It was not all work and no play during our time in Cardiff. We weren’t fantastically rich (what junior reporter ever is?) but we did get expenses for travel and meals and most journalists know expenses rarely leave you at a loss and generally at a profit.

We had nights out at the theatre and cinema and a small group of us even blagged our way in to the local casino which had a cabaret theatre above it.

I had a fiver in my pocket when we went in and that was a lot of money at that time.

When we left I had £25 ‐ a fortune.

The only gambling I had ever done was on slot machines in the Rhyl amusement arcades. Other than that I used to play cribbage with my grandfather for matches and Newmarket with Grandad and my elderly aunts when they came to visit.

That night I made two bets on the roulette table – first was just on red which doubled my pound stake and then I put two pounds on odds (still only risking my original pound stake).

Two safe bets and I was already up £3.

I shifted to the blackjack table and, never having been in a casino before, watched a few hands.

It looked like pontoon to me and that was something I had played with my Grandad and great aunts since I was knee high to a grasshopper.

Half an hour later my original fiver had four mates and I called it quits.

Before leaving we thought we might as well take in the midnight cabaret show upstairs.

It was a small auditorium, probably no bigger than the Little Theatre in Rhyl, and we were a couple of rows from the front.

It started off with a magician who was reasonable followed by a juggler who had his hands full with balls, clubs, knives and flaming torches – I kept my eye on the exit in case he missed one of the torches.

Then came the stars of show – a well-known TV double act quite high in the ratings at that time.

I was pretty certain I knew what the routine would be. This was an act often seen on family variety shows.

I obviously had not learned my lesson from Ken Dodd at Billy Williams’ Downtown Club.

I’m no prude but I was shrinking in to my seat after five minutes. I can’t think of one joke they told that night that I could possibly repeat.

I have never been able to watch that particular double act ever since – I still didn’t watch either of them when they split and did solo acts.

They’re both dead now.

I had a far better time when I met Morecambe and Wise a few years later and I was saddened when first Eric and then Ernie died.

Comedy is diminished by their absence.